A Simple Process for Taking on Non-Grantmaking Roles

Increasingly, funders are interested in taking on more catalytic roles within their communities, for example, working to change policies and systems in order to change the status quo for their grantees. Creative grantmaking can help them move in this direction. But without realizing the potential of their non-grantmaking activity – things like convening, advocating, training, or educating – foundations may be leaving significant value on the table and missing learning opportunities. To their credit, many funders today recognize that they possess substantial expertise, networks, and resources that can amplify the impact of their grants.

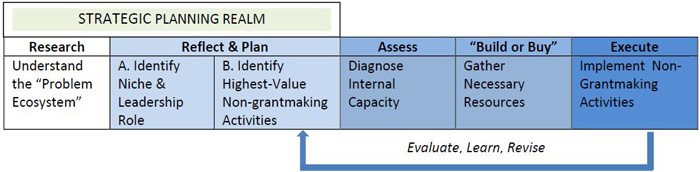

Turning that knowledge into action isn’t so easy. Funders contemplating “full mobilization” of their resources may be unsure how to start. It’s tough enough to run an effective and responsible grantmaking operation, without a whole new set of resources thrown into the mix! A simple process like the one below can help to organize thinking, cut down on the “overwhelm” factor, and increase chances of success (and sanity).

Process for Taking on Non-Grantmaking Roles

Research. The Omidyar Network’s guiding principle “problem first, tool second” reminds us to understand the factors influencing desired outcomes. Let’s say your focus is maternal health in Afghanistan. Start by following a pregnant woman from conception to birth. What support does she receive from government, private business, or NGOs, at what cost, and how does she access it? What is the quality of that support? What socio-cultural realities might affect her chances for a safe pregnancy and delivery? Are other funders working in this space? Putting the problem first in this way requires legwork upfront, but pays myriad dividends. It deepens your staff expertise and also helps you identify potential partners, understand what may be easy to change and what may be difficult, and select the right tools – both monetary and non-monetary. The Community Foundation for Greater New Haven took this approach with its recent strategic initiatives in immigrant integration and prisoner re-entry, conducting research on federal and state policies, social services, hometown associations, healthcare options, business interests, education, language access, and advocacy organizations before thoughtfully designing programs incorporating non-grantmaking roles. Rockefeller Foundation’s Search program takes the “problem first” concept to a uniquely robust level; it analyzed 11 topics in depth in 2013, drawing on staff, consultants and almost 200 outside experts.We can see from foundations that embrace this philosophy that the end game doesn’t have to be a formal plan. Regardless of how you kick the process off, try to establish an understanding of the purpose of your non-grantmaking activity, use that intentionality to inform consecutive steps that make sense, and strive for an inclusive approach that incorporates input from internal and external stakeholders. Smart foundations don’t conduct grantmaking in a vacuum and the same rule applies to non-grantmaking activities. Here’s how your process could play out:

- Reflect & Plan. Now that you have a solid grasp of the problem, examine your institutional personality and think about your current and desired position within the community. For example, are you generally more proactive or responsive? Do you seek visibility or do you prefer to work behind the scenes? What’s your risk tolerance? Foundations use strategic plans for grantmaking to determine where to play to strengths and where to take calculated risks, when to fund existing entities and when to “fill a gap” by assuming a champion role. While not everyone needs or wants a formal non-grantmaking plan, avoid decoupling non-grantmaking activities from your grantmaking strategy to leverage the impact of your dollars. The Cleveland Foundation has a great summary of how it considers its non-grantmaking roles of advocate, catalyst, convener, and leader.

- Assess. Once you’ve identified your niche and the non-grantmaking roles embedded in your job, it’s time to gauge your internal capacity. Internal capacity is simply your ability to put the plan into action, both in terms of personal capacity and foundation capacity. For example, if you want to complement your advocacy grantmaking with workshops, meetings with legislators, technical assistance, and webinars for your grantees (like the Missouri Foundation for Health), first do a reality check: do you have the people, skills, and knowledge you need? A diagnostic tool such as McKinsey’s OCAT or TCC Group’s FCCAT can help you take stock of your strengths and weaknesses across a range of relevant capacities. When approached in the right way, diagnostics can also be kickstarters for deep organizational learning.

- Build or Buy. At this point, it’s time to prepare yourself by acquiring the capacity you need for your chosen non-grantmaking roles. This could mean investing in some serious infrastructure, or it may be as simple as recognizing your current activities and untapped resources, re-organizing or consolidating them, naming them, and establishing a point-person to put ideas into action and provide oversight. For example, don’t assume convening stakeholders necessitates a large space for meetings; you may find creative workarounds using technology and social media. The Wikimedia Foundation recently piloted an online organizational effectiveness tool with suggestions on how Wikimedia-affiliated organizations with limited budgets can share existing resources and knowledge. Another good example of a lean approach is the Case Foundation – check out its helpful guide for virtual convening

- Execute…then Evaluate, Learn and Revise. When implementing your non-grantmaking activities, think about when and how you’ll measure the results of what you do. Collect quantitative and/or qualitative data, and build in reflection points along the way. Consulting stakeholders – the other actors in your “problem ecosystem” – is a good way to gauge the impact of your work and move beyond outputs to outcomes. When you can say with confidence that a particular non-grantmaking activity is working well or not (and why), it’s time to feed that learning back into your plan and revise as necessary. When you do have a big win, celebrate with everyone at your organization. Taking on non-grantmaking roles doesn’t have to be overwhelming, but does require some investment of time and energy across your organization; full mobilization means everyone has a stake in your success.

Funders: How have you approached non-grantmaking roles? Have they contributed to your impact? Have they changed your internal operations and culture?