Learning from Disruption: Two Case Examples of Resilience

Mass disruptions are likely to increase as communities seek greater social and economic equality and the climate crisis deepens. What wisdom can funders draw from the past 18 months to inform future strategy?

We are living at a profound moment in global history. COVID-19 has shaken the foundations of our economic, social, and health systems. No corner of society has been left untouched by the pandemic’s effects, including philanthropy. Indeed, we observed a common phenomenon during the onset of the pandemic and its ensuing turmoil: some foundation strategies struggled to find their footing while others adapted easily, enabling grantees to harness previously unanticipated opportunities to influence change.

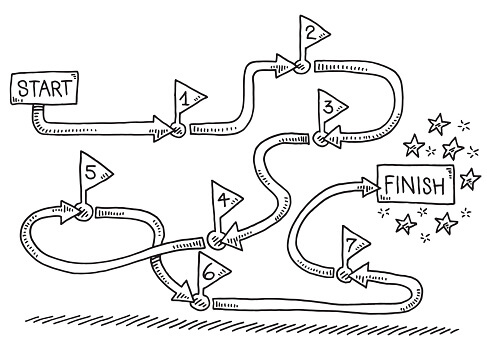

In this blog, we share two case examples to illustrate what makes some funding strategies more resilient than others — that is, when they support the ability of grantees to collectively achieve long-term aims amid significant disruptions in context. These case studies draw from a recent article that presents a more full analysis and theory about foundation strategies that are succeeding at adaptation vs. those that are struggling. At the core of this theory is the belief that, given today’s complexities, philanthropy must use its power differently — releasing control over organizations and their change strategies while using its unique position to work in solidarity with community leaders.

As the case examples illustrate, resilient strategies are characterized by the following:

- Address Systems, not Symptoms. Rather than focusing on the symptoms, these strategies focus on the causes of social inequities. Grantees seek to change how systems drive problems and reinforce historical patterns that lead to inequities.

- Support Networks, Not Solutions. Strategies that support grantees to take so-called “proven” solutions to scale are less effective in the face of disruption than those that resource networks of organizations that share a vision and hold multiple ideas about how to achieve change.

- Release Control over Pathways and Outcomes. Resilient strategies are ones that identify a problem and broad goal and provide grantees with the flexibility to pursue multiple change pathways and outcomes aligned with that broad goal.

- Focus on Transformational, over Transactional Capacity. Resilient strategies also build the capacity of networks, rather than individual organizations, to rapidly assess the external environment, select strategies and tactics, and work in partnership with others.

- Supplement, Don’t Supplant Community Power. Strategies are more resilient when funders activate their own power, not over grantees, but to resource grantees’ emergent ideas and solutions.

Art for Justice Fund

In our first case, the Art for Justice Fund purposefully created space for more than 100 grantees to gather and engage in immersive, interactive activities, fostering networking and collaboration, and celebrating progress and community. This launched a strong grantee network [2. Support Networks] of artists and activists working together to disrupt mass incarceration where members actively engage with one another online and through project collaborations.

While staff are clear about the Fund’s ultimate goals--reducing prison populations, promoting justice reinvestment, and changing the narrative around incarceration--grantees have wide latitude to define their own outcomes and tactics [3. Release Control]. Fund staff actively look for opportunities to support grantees’ leadership efforts, using its power to connect leaders with resources and to amplify and draw attention to their work [5. Supplement Community Power]. In addition, the Fund explicitly seeks to use the power and influence of its founder, art collector and philanthropist Agnes Gund, to inspire other art collectors to donate funding to reduce mass incarceration.

This flexible approach has worked well in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic. Overcrowding combined with the inability to quarantine or practice social distancing in jails and prisons presented a grave threat. Grantees adapted quickly, creatively, and effectively, drawing connections between the plight of prisoners to the larger public health and racial equity crisis [1. Address Systems] and sharing information with one another about what was and wasn’t working.

N Square

In 2014, the leading funders in the nuclear security space came together to invest in a new organization, N Square, with a goal of building a collaborative that would disrupt and stimulate innovation in a stagnating field of experts and advocates to accelerate the achievement of nuclear security goals. N Square, which focused on building a network of innovators [2. Support Networks], was initially housed within one of the funding partners, but was moved to an independent fiscal agent, giving it more freedom and flexibility [3. Release Control]. After a first year of active participation in many different levels of decisions, the funders agreed to be more selective about which decisions they would hold authority over and where they would let go and trust the Executive Director and her staff.

The funders, Executive Director, staff, and network partners have all steadily built their network development and systems skills, going through multiple processes to build an understanding of the types of organizations needed and apply systems sensing skills to assess what it would take to enable the field to operate more effectively. One of N Square’s signature interventions has been the creation of a network of fellows who are trained in design skills, systems thinking, innovation approaches, and more. These emerging and established leaders then prototype bold solutions for the nuclear security space, such as the SAFE Network, an innovation that harnesses non-classified data from a range of sources, analyzed by a network collaborators to identify the risk of nuclear proliferation or a nuclear crisis, with international diplomats, nuclear security experts, and former military leaders on standby to respond. Simultaneously, N Square worked closely with key organizations, helping to build their capacity for innovation and design [4. Focus on Transformative Capacity]. One of the funders leaned into this network, using its resources to create an Acceleration Fund managed by N Square to support emerging innovations [5. Supplement Community Power].

When the worldwide pandemic disrupted the in-person structures by which N Square steadily knits together the network and field, the team shifted very rapidly. Within weeks, they had identified not only the need to move to a virtual model, but also the opportunity to increase fieldwide competency in distance collaboration. In addition, they launched a futures and foresight training series designed to prepare leaders to manage uncertainty and better prepare for future disruptions [4. Focus on Transformative Capacity]. This program included decolonized methods and a partnership with the Black Speculative Arts Movement, helping build the community's resilience at a time when many were still reeling from the initial shock. They also retooled existing programs to work effectively online, taking advantage of unanticipated change to build a more substantial international network that collaborates seamlessly, both synchronously and asynchronously, across time zones.

Conclusion

In conclusion, resilience, as used here, does not mean a return to pre-disturbance status quo. Rather, the case examples speak to the inherent strength of a network of organizations working in concert to not only survive disruption but to redefine their approaches as opportunity permits – to bounce-forward, not merely bounce-back. We encourage foundations to consider these and other insights from the past 18 months as they plan and resource future funding strategies.