Catalyzing Collaboration and Innovation: How the Ralph C. Wilson, Jr. Foundation is Taking a Networked Approach to Building Nonprofit Capacity

How does a foundation spend down a $1.3 billion endowment in 20 years in a way that leaves communities stronger after the funding stops?

While there can be many approaches to spending down, for the Ralph C. Wilson, Jr. Foundation, investing in the capacity of nonprofits to better equip them to innovate and collaborate around complex social issues is a key strategy for

lasting impact.

The Ralph C. Wilson, Jr. Foundation was founded in 2014 through the bequest of its namesake, the late long-time owner of the Buffalo Bills football team. Before his death, Wilson handpicked four lifetime trustees and set a 20-year lifespan for the foundation.

The trustees decided to focus the foundation’s philanthropy on two regions that mattered most to Wilson—Western New York, the home of the Bills, and Southeast Michigan, where Wilson lived. With support from Rockefeller Philanthropy Advisors—a firm providing philanthropic advising, strategy and consulting services—the trustees chose four core areas for grantmaking—children and youth, young adults and working families, caregivers, and livable communities. The trustees prioritized capacity building as a key strategy for supporting livable communities.

“Initially the trustees were thinking about capacity building in terms of increasing efficiencies, drawing from their experiences in private equity and venture capital,” said David Egner, president of the foundation. “Over time they came to understand that efficiency is the wrong metric in the nonprofit sector, and it’s really about impact and giving organizations what they need to be able to innovate.”

As the foundation staff and board considered how best to spend down $1.3 billion by 2035 in two regions that comprise 16 counties and about 8 million people, they knew they needed to take a tailored approach for each region.

“There is a rich history of robust philanthropy in Southeast Michigan,” said James Boyle, vice president for programs and communications. “There are a number of foundations that invest in capacity building, and there is a network of intermediaries and service providers. As we looked at sources of support for nonprofits in Western New York, it was more limited. We know we can’t build the same things in Detroit and Western New York—it has to come from the community.”

Developing a Networked Approach to Supporting Nonprofits in Southeast Michigan

As Wilson Foundation staff considered the strategy for Southeast Michigan, they looked to the region’s burgeoning entrepreneurial sector for inspiration. Efforts to revitalize Detroit’s business economy provided models for a possible path forward. Egner and Boyle considered their previous experiences working together at New Economy Initiative, a project of the Community Foundation for Southeast Michigan that engages philanthropy in working to build an inclusive network of support for entrepreneurs and small businesses in southeast Michigan.

“The New Economy Initiative provided funding to incentivize behaviors we thought were critical to jump-start entrepreneurship in the region,” Boyle said. “In that work we wanted to understand, how do you get somebody who wants to grow or start their vision of what they need when they need it? And how do you continue to incentivize service providers to not hold anything to themselves for their own gain, but to collaborate, handoff clients, and work in a networked way that better serves entrepreneurs?”

One of the key outcomes of that work was BizGrid Live, an in-person networking event connecting entrepreneurs and the service providers in the grid. From this experience, Egner, Boyle and others saw the value of bringing people together in a physical space to provide opportunities for connection that may not have happened otherwise. “That was where the connectivity started,” Egner said. “For the first time we saw service providers pointing to each other and referring entrepreneurs to one another.”

As the team considered how to apply lessons learned from that previous experience to work with the region’s nonprofits, the foundation hired 313 Creative, a Detroit-based consulting firm, to facilitate a year of outreach to better understand local nonprofits’ needs and the role the foundation might play in strengthening the region’s nonprofit sector. From this outreach, they found that while there are many options for capacity building and technical assistance for nonprofits in Southeastern Michigan, these efforts are not coordinated.

The foundation also did a national scan for nonprofit innovation spaces—physical centers that provided technical assistance for and fostered collaboration among nonprofits. From that scan, the foundation organized a bus trip for 17 leaders in Detroit’s nonprofit sector to travel to Cincinnati to learn from efforts happening there.

“For the leaders that went on the trip, this was the first time they were able to spend time together this way,” said Shamyle Dobbs, executive director of Michigan Community Resources. “The actual road trip on the bus was valuable time together in addition to the opportunity to learn from other efforts in Cincinnati.”

A key takeaway from these experiences was the impact that the physical space has in allowing people to come together and generate ideas around solutions.

In 2017 the foundation decided to invest in the creation of a center to provide support for the region’s nonprofits. The vision for the center is twofold: 1) to create a space where nonprofits can convene, collaborate, and innovate around challenges facing the region as well as receive the capacity supports and assistance they need to be able to effectively deliver solutions; and 2) to foster stronger coordination and alignment among the region’s nonprofit service providers through support from center staff and the opportunity to come together in a central space. The center is housed on the ground floor of the foundation’s offices in Detroit because it is located in the region’s innovation district and because using the foundation’s space provided an opportunity to design the space from scratch.

“From an equity perspective, there is something to be said about nonprofits having access to a physical space where they can come together in the city and for the foundation to have a physical presence in the community as well,” Dobbs said. “The foundation is committed to being thoughtful about what capacity is needed to anchor the investment they’re making in our community.”

One area the foundation is trying to be particularly thoughtful about is striking the right balance between providing the support needed and ensuring the center operates with independence and has buy-in from the community.

“We are aware of the risks of being too close to the center as it gains trust in the community and gets off the ground,” Boyle said. “We want to provide center staff some distance while being supportive at the same time—a delicate balance that is an experiment for us. Through the process, we think we’ll learn some things about the relationship between grantees and funders that we can pass along to the community.”

Boyle said there are three components to how the foundation is thinking about supporting nonprofit capacity. “One is matchmaking between nonprofits and service providers to get nonprofits what they need, when they need it; two, bringing nonprofits together for facilitated problem solving; and three, culture—how can organizations connect in meaningful ways to build a culture of relationship, innovation, and trust?” Boyle said.

To achieve this vision, the foundation recognized it needed to partner with players with specific expertise and deep ties in the community. In addition, because the foundation is spending down, partnering with other organizations is critical to the long-term sustainability of the center.

“We can provide something that’s disruptive, but then that work will be done when we spend down,” Egner said. “If we’re building partners, this work has a shelf life that’s much

longer than 20 years. And there is so much expertise already in the community.”

Over the course of the exploratory year, three organizations emerged early as partners to get the work off the ground:

- TechTown—a nonprofit that supports entrepreneurs and small businesses through a co-working, meeting and event space. The center is now a project of TechTown. TechTown is staffing the center, designing the programs and managing the architectural buildout. The foundation has provided a three-year, $4.75 million grant to support the first years of this work.

- Michigan Nonprofit Association (MNA)—a membership organization serving the state’s nonprofit sector. MNA will support capacity assessments for nonprofits using a tool they’ve developed and tested over 20 years to help organizations identify strengths, goals, and priority capacity needs. The foundation provided MNA a $315,000 grant over two years to provide this service to guests.

- Michigan Community Resource (MCR)—a nonprofit providing pro bono and low-cost legal and other professional services to nonprofits serving low-income individuals and communities. MCR is partnering with MNA, Nonprofit Enterprise at Work, and University of Michigan Technical Assistance Center to create a referral system that will help guests to the center find service providers that are best suited to meet their needs. The foundation provided $255,000 to support the first year of this work.

While these initial partners brought the skills, expertise and relationships critical to launching the center’s services, additional partners are joining the efforts to meet additional needs as they emerge. For example, providers such as Data Driven Detroit are available during set hours each week to consult with nonprofits on aggregating and using data.

“This is the first time these organizations have come together around a common vision,” Dobbs said. “I’m excited for this collaboration—especially during a time where funding can drive competition. This is an opportunity for us to align our resources to imagine what the possibilities could be when we are working together.”

In addition, the foundation wanted to ensure it was learning from what others in philanthropy know about facilitating partnerships and best practices in capacity building. To meet these needs, the foundation hired Community Wealth Partners, a social sector consulting firm, to provide facilitation and backbone support to the partnership, to share national best practices on capacity building, and to help the partners think about how to measure impact of the center and its services. Community Wealth Partners facilitated a series of five meetings among the partners to create a vision for the types of services the center would offer—informed by a national scan of related efforts, vetted tools from each of the partner organizations to inform which tools the center might share with users, and supported the partners in thinking about how they will assess the impact of

the center.

To the foundation and TechTown, attention to detail in planning the physical space is a critical factor in invoking a spirit of innovation and collaboration.

“The foundation recognizes that the majority of nonprofits in Detroit—as is true in most places—are operating from a mindset of scarcity,” said Mariam Mansury, senior consultant with Community Wealth Partners. “Nonprofits are chronically understaffed, under-resourced and overworked. Through the center, the foundation is trying to create an atmosphere that fosters a mindset of abundance. Their thinking is, if nonprofits can get out of a scarcity mindset, they will be more open to collaboration and better able to come up with more innovative solutions to the issues they seek to address. A place-based center that fosters collaboration and innovation and provides technical support can help instill an abundance mindset rather than a scarcity mindset.”

In April 2018, a hiring committee with representatives from the foundation, TechTown, Wayne State University, City of Detroit, Nonprofit Enterprise at Work, and Michigan Nonprofit Association hired Allandra Bulger to be the center’s first executive director. Foundation staff ceded decision-making authority and oversight of construction and planning to Bulger once she stepped into the role.

“The overarching idea is to have a space that is open and fosters collaboration and shared learning,” Bulger said. Key elements to facilitate collaboration include flexible meeting spaces that can be adapted to meet a variety of needs, meeting technology in every room, and a centrally located kitchen to invite informal connections. In addition, the center has looked for opportunities to engage the community in co-designing the space. Staff have decided to intentionally leave some places flexible so they can be open to additional feedback and adapt to users’ needs once guests are actually using the center.

“Often community engagement is a one-time activity or a box that’s checked,” Bulger said. “I don’t believe in the idea that if you build it they will continue to come. If you build something folks might come, poke around, and see what it is, but for folks to truly engage in the center they have to see themselves in that space. They have to be part of cocreation.”

To engage the community in that cocreation, Bulger has sought engagement on everything from programs and services, logo and brand, to the name for the center itself—Co.act Detroit.

The center aims to be a welcoming place for any nonprofit in the region to reflect on organizational strengths and challenges, meet with other organizations, and receive support finding technical assistance. Bulger and her team have engaged a range of nonprofits from small grassroots organizations to large intermediaries to help shape the vision.

A soft launch of Co.act Detroit took place in December 2018, followed by the launch of a few programs and services in January. Using feedback from the visioning process, programs launched include one-on-one consultations on specific capacities such as data use and aggregation or legal issues and accounting (similar to office hours), workshops and trainings on similar topics, and networking events. The center will launch additional programs and services in the future, also based on input from local nonprofits.

In addition to these programs, nonprofits who come to the center have an opportunity to complete an organizational assessment, facilitated by Michigan Association of Nonprofits, be paired with a coach to help organizations prioritize areas to work on—based on assessment results— and find technical service providers for customized capacity-building support to help them meet their goals.

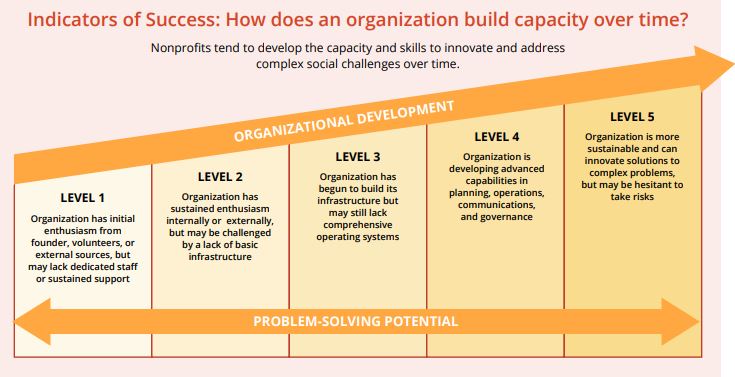

Co.act Detroit hopes to help nonprofits to build their capacity so that over time they become better equipped to innovate and address complex social challenges. They think about this evolution on a five-stage continuum (see graphic).

To help organizations access services needed to build their capacity along this continuum, the foundation has established a one-year, $1.5 million fund to provide grants of up to $50,000 to eligible organizations to help them pay for customized capacity-building services. Staff of the center will administer the fund, with input from an advisory committee comprised of local intermediaries. The initial fund is a pilot, and the foundation will seek to learn from the initial experiences to inform its future approach.

Over time, the foundation hopes to see more funders in the region supporting the ongoing costs of running the center and the costs nonprofits incur in accessing services. This will depend on the value-add the center ends up providing the region’s nonprofit sector. While it’s too soon to determine the value-add yet, Kelley Kuhn, vice president of Michigan Nonprofit Association, thinks the center will support the local nonprofit sector in a number of ways.

“The biggest value the center is going to bring to nonprofits in the region is a place where services they need to build capacity are coordinated,” Kuhn said. “A second opportunity comes with the focus on innovation and encouraging nonprofits to focus on what’s already working, collaborate and brainstorm with others, and think big about what they could do. Finally, having a physical space where this training, collaboration and innovation can happen is going to provide great opportunities to connect like-minded people with one another for greater collaboration and impact.”

As the foundation seeks to assess the impact the center is having on the region’s nonprofit sector, it will track outcomes on three levels—1) guest experience, 2) organizational capabilities for the center itself and the organizations accessing services, and 3) network and system impact.

Potential metrics include the following:

- Guest Experience

- Satisfaction rates among guests and service providers

- Increased knowledge and skills among guests

- Increased ability to implement organizational change

among guests - Number of referrals

- Organizational Capabilities

- Center capabilities:

- Increased funder interest

- Increased ability to implement programming

- Guest capabilities:

- Adequate funding to cover basic organizational needs

- Implementation of a strategic plan

- Presence of a risk-tolerant mindset

- Presence of an effective board of directors

- Increased retention and recruitment of top talent

- Network and System Imapact:

- Increased nonprofit ability to collaborate with other organizations to have greater impact

- Increase in partnerships

- Increase in national funder support of local nonprofits

- Improved regional outcomes around issues such as health, education, and infrastructure

- Center capabilities:

At a higher level, Boyle says the foundation will be looking for two things as indicators of long-term success. “Have we created a model that has demand and that nonprofits and foundations want to support to ensure its long-term sustainability? On a broader level, wouldn’t it be great if we had stories of success that came from our work to help our region’s nonprofits be able to operate in more nimble, collaborative ways?”

Building Capacity in Western New York

To determine its strategy for investing in Western New York, the Wilson Foundation formed a collaborative with five funders of various sizes and types, and two local consultants with deep ties to the region to develop a collective vision for the work. The foundation hired Community Wealth Partners to facilitate collaboration and provide communications and project management support for the group.

As the Wilson Foundation has entered this work in Western New York, staff have tried to be mindful of the fact that they are the new funder in town, the power they wield by their significant asset size, and lessons learned from their experiences in Southeast Michigan. A key lesson learned is the importance of patience and humility when working in collaboration.

“In Detroit, the pressure of time we feel as a spend-down foundation gave us a sense of urgency that made us want to skip over process,” Egner said. “But process matters, and we learned we had to slow down to work in better partnership with others.”

Lifting Up Common Themes to Inform Capacity-Building Practice

As Wilson Foundation staff reflects on their experiences in both Southeastern Michigan and Western New York, they recognize some similar steps that have proven to be vital to making progress toward building a stronger nonprofit ecosystem in both regions:

- Leveraging assets in communities. In both instances, the foundation and its partners have worked to have a full understanding of strengths and resources that already exist in the region. The foundation is committed to finding ways to add value to the regions that build on the opportunities that currently exist, rather than trying to force something that doesn’t fit the community’s assets and needs or duplicating preexisting efforts.

- Working with intermediaries. Intermediaries with deep ties to the community are powerful partners in the foundation’s approach to developing a more networked nonprofit ecosystem in both regions. In Detroit, the foundation has partnered with intermediaries like TechTown, Michigan Nonprofit Association and Michigan Community Resources to design the Center for Nonprofit Support and deliver its services. Part of the vision of the center is to foster greater coordination and collaboration among other intermediaries as well. Members of the collaborative in Western New York agree that however the work there unfolds, it should be driven by a desire to leverage what intermediaries currently offer and to foster greater connections between nonprofits and the resources available.

- Engaging community in the work. The Center for Nonprofit Support aims to create direct touch points with a diverse array of nonprofits and community-based organizations throughout the region. Staff engaged in shaping the vision for the center have been intentional in reaching beyond the usual suspects for input. Similarly, the work in Western New York is starting with community engagement. “The collaborative has hired a local consultant to go out and talk with nonprofits with a strengths-based frame,” said Sandra Moore, associate director with Community Wealth Partners. “Where do they feel strong? What are their needs, particularly around capacity building? What additional support would allow them to better deliver on their missions?”

- Connecting nonprofits with the resources they need. A persistent capacity-building challenge for nonprofits is identifying and vetting service providers to find the type of support they need. The Center for Nonprofit Support is built around a vision of providing nonprofits with vetting and referral assistance, through coaching and support from Community Resources Michigan. “The nonprofit ecosystem in Southeast Michigan is strong, with lots of foundation support, lots of nonprofits, some good collaboratives happening, and some good intermediaries,” Kuhn said. “The value the center is adding is helping coordinate all those players in that ecosystem to better serve nonprofits.” This type of connectivity is part of the value the collaborative wants to provide to nonprofits in Western New York as well.

- Ensuring long-term sustainability. From the start, the Wilson Foundation has been acutely aware that it is infusing a significant amount of resources into two relatively small regions over a discrete period of time, and it is important to take measures to ensure the regions have what it takes to sustain these investments for the long-term. A focus on building capacity of organizations in the region has been one strategy to help ensure long-term sustainability. “As part of our spend-down mandate, we’ve got to build capacity of the nonprofits in our regions,” Egner said. “If we don’t help build these organizations so they can effectively absorb the capital we’re injecting into the community, we won’t have any impact.” A second strategy for ensuring sustainability is to build partnerships so that there will be other organizations to carry the work forward after the foundation sunsets.

- Sharing power with partners and community members. In the Western New York collaborative, the foundation has taken intentional steps to try to manage power dynamics in the group. For example, the group makes decisions on consensus, and everyone in the group has an equal vote, regardless of how much money they are bringing to the table. When making grants to work with consultants, the foundations in the group have pooled their money to cover the costs, and each foundation’s payment is proportional to its asset size. In the creation of the Center for Nonprofit Support, the foundation has ceded decision-making for the design of services and offerings to TechTown and the staff they’ve hired to run the center.

While the Ralph C. Wilson Jr. Foundation is still in the early stages of its 20-year strategy, staff hope that the partnerships they are putting in place in both regions will help ensure the foundation’s investments have lasting impact.

“I think the Wilson Foundation has the potential to make significant contributions to the strength of our nonprofit community over the next 20 years,” said Beth Gosch, executive director of the Western New York Foundation. “If the foundation can help us identify the talent and vision in our communities that will result in change, and support and develop that talent and vision, that will have lasting impact.”

Discussion Questions: Use these questions to guide discussion with your colleagues

and explore ways you might be able to support capacity building among your grantees.

- What from the Ralph C. Wilson, Jr. Foundation’s story resonates with what we have learned from our work with grantees? What about their approach is different from what we have done in the past? What is something we might consider trying based on this approach?

- What are our grantees’ capacity-building needs, and how do we know? What are we already doing to meet these needs, and what more might we do?

- What opportunities currently exist for nonprofits to connect with one another in our area? Where have we seen examples of nonprofits coming together to identify new solutions? Where might there be an opportunity to foster greater collaboration and creativity among our grantees? How might we do that?

- What are the barriers to increased investment in this type of work within our foundation, and how might we address them? To whom do we need to make the case, and what arguments would they find most compelling?