Strengthening Fundraising Capacity: How the Evelyn & Walter Haas, Jr. Fund is Supporting Innovation

Editor's Note: This case study is one of five in a suite of case studies focused on building grantee capacity using the support of consultants. Each case study has been developed in partnership Community Wealth Partners, drawing on their capacity-building work with various funders and grantees. The case studies showcase varied approaches taken to address the long-term capacity needs of grantees, giving insight to the philanthropy landscape and strategies for foundations, consultants, and practitioners.

Ask a nonprofit executive director what keeps her up at night, and chances are, “fundraising for the organization,” will be near the top of the list.

“Fundraising wasn’t empowering work,” said Angelica Salas, executive director of Coalition for Humane Immigrant Rights-Los Angeles and a grantee of the Evelyn and Walter Haas, Jr. Fund. “It felt like something you had to do, you didn’t really want to do, and yet your job and the organization’s health depended on it.”

Daring to Lead, a 2011 survey from CompassPoint Nonprofit Services, found fundraising to be the number one contributor to burnout among nonprofit executive directors and a reason many were considering leaving the sector altogether.

These findings are not new. Financial Sustainability has long been a challenge for many nonprofit leaders. For the Evelyn and Walter Haas, Jr. Fund, supporting their grantees’ fundraising capacity and trying to help improve the support available to them has become a core feature of their investments in strengthening nonprofit leadership.

Gathering Data to Inform A Deeper Understanding of the Problem

For more than 15 years, the Haas, Jr. Fund has invested in leadership in the nonprofit sector. A key component

of the Fund’s investment in nonprofit leadership is its Flexible Leadership Awards (FLA), a program that consists of three elements:

- Flexible, long-term funding so that nonprofit leaders can decide how they will use it to address leadership challenges over three to five years;

- Peer learning to share ideas and solutions with other leaders through a foundation-facilitated cohort of FLA grantees; and

- Strategic advice from a consultant the foundation matches with grantees to help them develop and implement a leadership development plan.

Through conversations with FLA grantees, the Haas, Jr. Fund heard repeatedly that fundraising is a major challenge for nonprofit leaders, and that it stifles creativity and strains relationships both inside and outside the organization. In fact, support for fundraising was one of the most common ways FLA grantees opted to use the flexible funding they received.

“Fundraising was a chronic pain point for grantees, and we weren’t helping them solve that challenge as clearly as the other ways we were helping support leadership,” said Rachel Baker, director of field building at the Haas Leadership Initiatives.

To better understand the ways in which fundraising contributes to leadership challenges inside nonprofits, the Haas, Jr. Fund funded research led by CompassPoint Nonprofit Services in 2013. In a national survey of more than 2,700 nonprofit executive directors and development directors representing a range of organization types and sizes and 11 focus groups held across the country, the UnderDeveloped study lifted up some key challenges:

- Difficulty recruiting and retaining development directors. The study found that half of development directors expected to leave their job in two years or less, and 40 percent are not committed to careers in development. When there are vacancies in the development director position, it takes an average of six months for organizations to fill them.

- Dissatisfaction with the caliber of talent among candidates. More than half of executive directors said their most recent search for a development director produced an insufficient number of qualified candidates. A significant number of executive directors said their development directors are lacking in key fundraising skills. A significant number of development directors also said the same about their executive directors.

- Failure to recognize fundraising as a core leadership function. Almost one in four nonprofits has no development plan in place. Three out of four executive directors say their boards are not doing enough to support fundraising. A majority of development directors report only little to moderate influence on key activities such as getting other staff involved in fundraising and developing organizational budgets.

A key recommendation pulled from the report is for nonprofit and philanthropic leaders to work together to change the lack of recognition of fundraising as a core leadership function and help others see it as an integral part of the organization’s work. The report found that most organizations placed too much responsibility for the organization’s financial success solely on the shoulders of development directors. A better way forward, the report suggests, is to break down the silos that often happen between fundraising and programs and create more shared responsibility for tending to a ‘culture of philanthropy’ inside organizations.

Advocating for Broader Support for Fundraising Capacity

In the years that followed, the Haas Jr. Fund and CompassPoint used the UnderDeveloped report to catalyze a national dialogue about fundraising challenges so many organizations face.

“We did not expect the report to go as viral as it did,” Baker said. “For years we’ve heard feedback from a range of organizations and networks that have used the report to support internal conversations, board development work, and strategic planning. It really hit a nerve in the sector.”

In 2016, the Fund commissioned two additional reports to dig deeper into two key questions. Beyond Fundraising explores the concept of a “culture of philanthropy” and how that might play out inside organizations. Fundraising Bright Spots seeks to learn from the successful experiences of small- to mid-size organizations raising money from individuals.

In addition to the published reports, the Haas, Jr. Fund conducted a scan of training resources available for development directors for internal purposes. That research revealed that while there are plenty of offerings to cover fundraising fundamentals and technical training, higher- level professional development related to fundraising is harder to find.

The research confirmed what the Haas, Jr. Fund was learning from its grantees: the nonprofit sector does not invest in development directors as leaders because there is not broad recognition of fundraising as a core leadership capacity. As a result, development directors are not receiving professional development to help with the adaptive skills and leadership competencies the role requires.

“The data suggested this was a systemic problem,” said Julia Ritchie, director of strategy and special initiatives for the Haas Leadership Initiatives at the Haas, Jr. Fund. It pointed the Fund to support nonprofits in taking a more integrated, holistic approach to development—which they referred to as building a culture of philanthropy inside organizations—and to provide leadership development support to development directors that goes beyond basic technical skills.

A Milestone Moment for Mobilization

The election of Donald Trump in 2016 brought a seismic shift for many nonprofits across the nation—in particular for organizations working for causes that seemed to be in jeopardy under a new administration. Executive orders on immigration that affected some organizations’ constituencies, shifts in federal funding, and steep increases in demand for services in areas including reproductive, immigrant, LGBTQ, and environmental rights have left many nonprofits scrambling to respond. At the same time, many organizations have experienced a surge in volunteers and donors. For example, the ACLU received $24 million in donations—six times its yearly average—in just a single weekend after the White House announced its first executive order limiting entry and reentry among specific groups of immigrants and refugees. Greenpeace and Sierra Club reported a surge in volunteer sign-ups and donations in the months following the election. When the Haas Jr. Fund reached out to its grantees—many of whom work in support of immigrant and LGBTQ rights—they heard of similar experiences.

While an increase in interest and support offers exciting opportunities for nonprofits, many of them lack the capacity and resources to respond nimbly to these opportunities and fully leverage them. For example, some nonprofits lack the technology tools and digital engagement strategies needed to most effectively respond to the surge in interest in donations. To leverage a surge in interest, nonprofits need to be able to do things like provide clear and easy ways to donate, capture new supporters’ contact information when they engage with the organization through social media, and build relationships by continuing to give them opportunities to engage meaningfully in the mission. Further, when fund development work is viewed as a technical function and siloed within the organization, nonprofits can miss an opportunity to turn what might be a momentary interest in the organization into a longer and deeper relationship. This approach integrates communications, fundraising, and advocacy in new ways.

With this knowledge and a heightened sense of urgency in the wake of the election, the Fund wanted to know how it best could help its grantees and their stakeholders. Consistent with the Haas, Jr. Fund’s usual practice, it began by engaging them in the conversation.

Co-Creating Solutions with Grantees

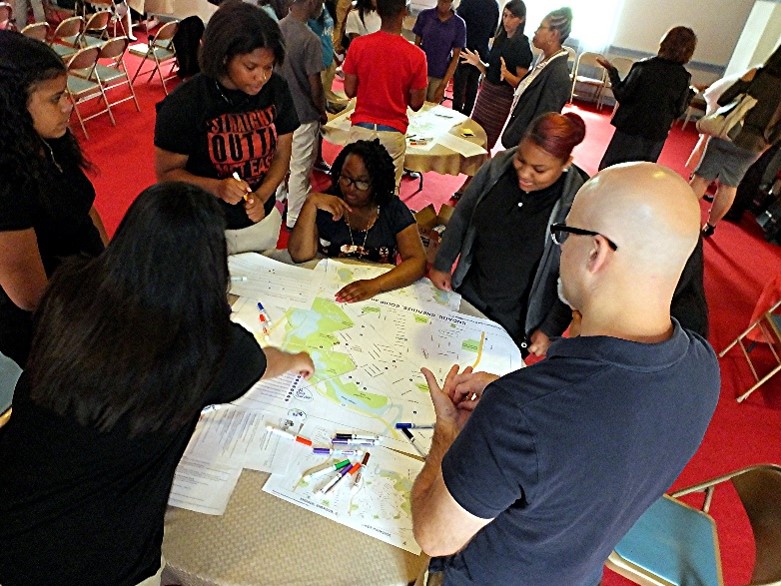

In early 2017, the Fund convened grantees to better understand how the post-election environment was affecting their fundraising needs and to explore possible solutions together. The Fund hired Community Wealth Partners, a social-sector consulting firm, to help with the design and facilitation of two half-day gatherings—called Design Labs—of about 50 grantees representing a cross-section of the Fund’s overall portfolio.

The Haas, Jr. Fund and Community Wealth Partners brought a human-centered design mindset and methodology to the lab design. Human-centered design approaches seek to tap into the creativity of individuals and groups to create innovative solutions to challenges. Their objective was to use past research to ground the conversation, engage nonprofit leaders in generating ideas for building fundraising capacity among nonprofits, and foster peer connections.

“Design thinking methodology is not easy. It’s not typically quick,” Ritchie said. “We did a little bit of adaptation in the methodology. Getting people to think creatively in times of stress is really hard. When you bring people into a design process, they don't always know what is possible."

To try to foster more creative thinking, the Haas, Jr. Fund and Community Wealth Partners integrated tactile features like working with art supplies and incorporating physical movement into the meeting design.

Another key consideration in planning the Design Lab was being sensitive to the demands on grantees the Fund was asking to participate. “We paid them to participate; we didn’t ask them to do this for free,” Ritchie said. “We also created a packet of fundraising resources as a token of appreciation for giving us their thoughts and time.”

A key theme that emerged from the Design Lab was challenges related to equity and diversity in fundraising. “We heard from several leaders of color about challenges with fundraising due to complex relationships with money and lack of access to high net worth networks,” said Isabelle Moses, director with Community Wealth Partners.

“There’s been a false dichotomy between social justice and money,” said Matt Berryman, executive director of Reconciling Ministries Network, one of the grantee organizations at the Design Lab. “We all have adverse reactions to the way money and power are intertwined in some oppressive structures. But we have to acknowledge that we can’t do our work without money.”

Another theme that emerged, related to these psychological barriers and issues of equity, was the notion of a scarcity mindset. “There was a desire to shift the nonprofit sector from a scarcity mindset to an abundance mindset,” Moses said. “When this happens, we imagine a different dynamic between funders and nonprofits—one where funders and nonprofits bring a spirit of partnership to generating solutions and delivering financially sustainable programs. An abundance mindset would also enable nonprofit leaders across organizations to proactively work together to develop collective approaches to solving problems, and that foundation funding practices would inspire collaboration over competition.”

Data from Nonprofit Finance Fund’s 2018 State of the Sector survey helps show why nonprofits are in a scarcity mindset. The survey found that the top challenges nonprofit leaders face are achieving financial sustainability for the organization and offering competitive compensation for staff. In addition, 86 percent of survey respondents said they are experiencing an increased demand for services, and 57 percent said they can’t meet the increase in demand.

A third theme that emerged from the conversation was related to the quality and type of consulting support available for supporting fundraising capacity. Grantees’ experiences with fundraising capacity support were consistent with what the Haas, Jr. Fund found in its own landscape scan.

“The capacity building field is largely made up of subject experts,” Ritchie said. “Unintentionally, many capacity building practitioners reinforce the very silos that we are trying to break down in organizations. For instance, strategic planners who don’t include a revenue or business plan. Fundraisers who think only of the tactical solutions to fundraising, but don’t think about the leadership and cultural practices that are needed to build and sustain fund development.”

With this insight in mind, the Fund realized a key way it could help grantees with their fundraising challenges was by helping strengthen the systems of support available to them.

Collaboration with Capacity Builders to Improve Practice

In fall 2017, the Fund partnered with Community Wealth Partners again to design and facilitate a three-day Innovation Lab that included a range of fundraising, strategy, and financial management consultants, executive coaches, movement builders and nonprofit leaders. Their focus was to collectively explore how to help build a culture of philanthropy within the nonprofit sector. The lab again included human-centered design methodologies and graphic recording to spark creativity and collaboration.

Service providers walked away from the Innovation Lab with personal commitments about new approaches they can put into practice in their work.

For participant Jodie Tonita, co-founder and executive director of Social Transformation Project, the lab underscored for her the importance of ensuring the development directors she works with have the right environment in which to succeed. “It can’t be just about training one individual and then popping that person back in an organization,” Tonita said. “We need to make sure the organization is creating space for the development director to thrive.”

The Innovation Lab gave Mario Lugay, founder of Giving Side, a chance to test out emerging ideas for how to take more collaborative approaches in his fundraising consultancy to help ensure the collective sustainability of organizations working on common issues. “I am trying to work on a project to reimagine the thank you letter,” Lugay said. “Why not use it to say here are three other groups we need to succeed for us to succeed, and can you support them as well?”

The Innovation Lab gave the Haas, Jr. Fund new insights on how they can best support the field as well outside of offering peer learning spaces. Since the gathering, the Fund has invested in three strategies. The first is supporting in-depth leadership development for senior fundraising professionals by partnering with Rockwood Leadership Institute to create a new fellowship called Resource Leaders, which will start in 2019. The goals of the fellowship are to reposition development directors as senior organizational leaders and strategists, cultivate their leadership skills, provide tools and resources for embedding fund development inside organizations, and creating a learning community for fellows. The fellowship includes two week-long residential sessions, webinars, coaching, and consultation.

“Development directors rarely have time to think deeply about their personal and professional path,” said Mary Nemerov, chief advancement officer at the Sierra Club and a Resource Leaders alum. “My Rockwood experience provided a better perspective on my work and my life and powerful new peer relationships.”

As a second strategy, the Fund is investing in building the capacity of grantees to engage new supporters and raise more money in the digital era. As the experiences of many nonprofits in the wake of the 2016 election showed, organizations need to master a range of approaches for raising money, recruiting supporters, and getting their message out. While the more traditional methods such as galas and year-end mailers are still important, the digital era has brought about new methods that are equally important.

To help nonprofits build these capacities, the Fund launched the M3 Initiative (Message, Mobilize, Money). Through the initiative, the Fund hired two consulting firms with specialized skills to provide capacity-building assistance to 16 organizations working on immigration rights and LGBTQ rights. M+R Consultants is working with eight immigrant rights organizations in California, led by the California Immigration Policy Center. PowerLabs and Network for Good are providing capacity-building support to eight organizations working on LGBTQ rights, led by the Equality Federation.

These consulting firms have deep experience in digital engagement strategies that were honed in political campaigns. Through the cohorts, the firms have worked closely with teams of fundraising, communications, and program staff at each organization to help them develop integrated digital strategies that create a ladder of engagement for supporters.

“Firms with this type of expertise may have worked with national campaigns or very large nonprofits, but typically they haven’t been accessible to smaller organizations,” Baker said. “Having a funder pull a cohort together makes it possible for these firms to reach organizations that previously had been out of their purview. We hope to share what we’re learning from these cohorts so that it can benefit the field as well.”

“I see the integration of these things [money, mobilize, message], more clearly than I ever have in terms of our work,” said Chris Mueller, who supports PICO-CA’s communications efforts. “We are starting to get into a good rhythm of how we integrate fundraising with social media and messaging and how we connect online action to offline action and fundraising.”

In addition, the Fund has continued to play a modest role in supporting innovation, collaboration, and connection across the network of capacity builders who were part of the Innovation Lab. For example, connections have been fostered through group email communications and some spot funding opportunities for activities that promote collaboration among consultants on the theme of a culture of philanthropy, such as attending training on culture change together. From time to time, the Fund has shared interviews with one group member to help members get to know one another a bit better, announcements of upcoming events of interest, and announcements of funding opportunities for conference registrations or other professional development when available.

The investment is paying off. Members of the group have come together to organize workshops, speak together at conferences and pilot new programs, all aimed at helping foster a culture of abundance. “Practitioners rarely have time to be together in a collaborative, generative way,” Moses said. “There is little space for being in conversation with each other about how to shape practice, so opportunities like these are valuable for practitioners and can have a multiplier effect as they engage with and influence organizations across the sector.”

Other practitioners are also championing a culture of philanthropy and an abundance mindset. For example, CompassPoint Nonprofit Services has been facilitating learning communities based on their Bright Spots research that focus on changing cultures around fundraising.

“One headline we’re seeing is that groups are wrestling with how to create a mindset for all staff around fundraising being core to an organization’s identity,” said Steve Lew, project director at CompassPoint. “Beyond mindsets, it gets to the question of addressing structures and power dynamics so that non-development people can have the time and support—and the authority—to manage relationships with donors. We’re finding you can create more staff buy-in for this work when people have more control and understanding of their budgets. They know the true money needs of the organization, and they start to see fundraising as more critical to their work.”

When an organization embraces a culture of philanthropy, the work of the development director shifts from isolating to inspiring, and the potential impact expands. “Talk about fundraising as a shared work,” said Angelica Salas. “When we add all these incredible people inside our organization, the circle expands.” It is this mindset shift the Fund hopes to see take hold in the field.

“Lately we’ve been framing it more as a question of how do we resource social change?” said Rachel Baker. “That means shifting funders from giving a little grant to help an organization with fundraising to having everyone consider what is our role around how social change is resourced? We’d like to see everyone lift up from a technical lens on the challenge to what we see as a bigger issue.”

“In foundation funding, we know that very little goes to investing in the capacity building of grantees. Within that, even fewer support nonprofits to build their fund development capacity,” Ritchie said. “We are excited to see the conversation start to take off among funders and hope to generate more investment in strengthening this core competency.”

Discussion Questions: Use these questions to spark discussion within your own foundation to explore ways you might be able to help build a culture of philanthropy among your grantees.

- What from the Haas, Jr. Fund’s story resonates with what we have learned from our work with grantees? What about their approach is different from what we have done in the past? What is something we might consider trying based on this approach?

- What challenges do our grantees’ face related to financial sustainability? What types of support do they need to help overcome these challenges?

- What types of technical assistance is available to grantees to help them build their fundraising capacity? To what extent do offerings available help develop the leadership skills of senior fundraising professionals? How might funders help grantees adapt to rapid and dramatic changes in the funding environment, like the proliferation of online and digital communication strategies?

- How are we influencing the practice of capacity builders who regularly serve our grantees? What are ways we can support greater alignment and shared practices across the field of providers?

- What are the barriers to increasing investment to support grantees’ fundraising capacity within our foundation, and how might we address them? To whom do we need to make the case, and what arguments would they find most compelling?